|

We have no control over our social status at birth. Does this dictate our lives, or can we change our status? If we can, does this improve our health prospects and our life expectancy? |

What is status?

Status is our social or professional standing. This is sometimes also described as our socioeconomic status and can be determined by:

- Our birth i.e. inherited status (ascribed status). If you are born into a royal family, for instance, you start life with a high status.

- Our own success (achieved status). This depends on what we achieve in our lives, for example through education, at work, in our families and communities or in other fields (such as sport, music or volunteering), and possibly even who we marry.

How status works in practice isn’t necessarily straightforward. For instance, a plumber may earn more than a junior doctor or a retired professor but is often seen as having lower social status. This suggests that our views of social status are probably stronger than our views of economic status.

Other factors also apply. For instance, in some societies old age confers status, whereas in others societies age-related retirement may mean a loss of social status. The impact of this status may also vary according to ethnic origin. This was one of the findings from a review of studies published in the BMJ in 2016.

What has social status got to do with health?

Our status is thought to affect both our life expectancy and how many years of good health we are likely to enjoy.

Why might status make a difference?

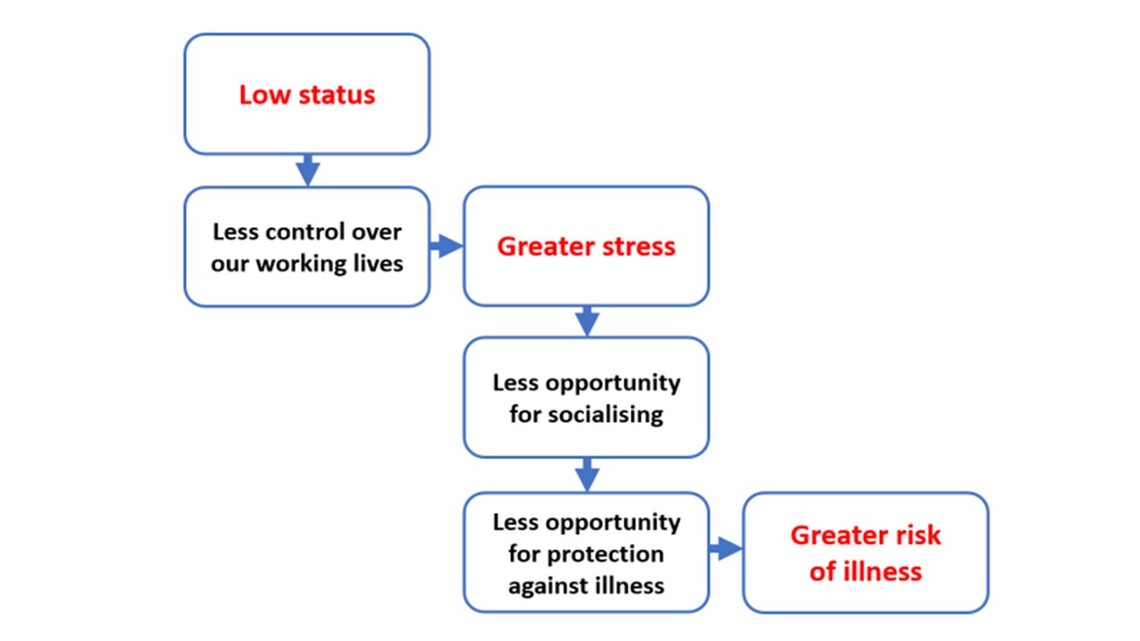

Sir Michael Marmot, Professor of Epidemiology and Public Health at University College London, is an expert in health inequalities. More than 30 years of research have led him to conclude that social status influences how long we live.

He explains that the lower our status, the less control we have over our working lives. Less control results in greater stress which in turn reduces the opportunities for social participation. He believes that this combination means less protection against illness.

Is there evidence that higher status leads to longer life?

In 2019, the UK’s Office for National Statistics reported that males were living 8–9 years longer and females 6–7 years longer in the most affluent London boroughs (Westminster, and Kensington and Chelsea), where more people might be expected to have higher socioeconomic status, compared with their counterparts in the most deprived towns (Blackpool and Middlesbrough).

What can we do to avoid status becoming a life sentence?

There are several ways in which we can raise or compensate for our social status and improve our chance of living a longer and healthier life:

- Through our own achievements

- Being part of social networks and by integrating into society

- Volunteering

- Being happily married

- By engaging with the creative arts

Below is some evidence for each of these approaches to improving socioeconomic status, and therefore also to living a longer and healthier life.

- Between 1924 and 1984 there were five general secretaries of the Trades Union Congress (TUC). They lived to an average age of 80; well above average for that time. All were from working class backgrounds, such as Len Murray the son of a farmworker. However, they achieved higher socioeconomic status through their own efforts. This is a small sample, but it fits the pattern and suggests that one option is to improve our status through what we achieve in life.

- Studies have shown that being part of a social network may help protect us from poor health if we were born into a low socioeconomic status. For example, a 2015 review of four long-term studies concluded that social integration had a number of physical health benefits, while being socially isolated had adverse effects on health – for instance being worse than diabetes for blood pressure in later years. Research has found that the lack of social connections increases the odds of death by at least 50%. This is comparable to the harmful effects of smoking and exceeds those of many other known risk factors of mortality such as obesity or physical inactivity.

- Volunteering could benefit our social status by providing a new role and new social networks. While more research is needed, early investigations suggest volunteering improves longevity.The evidence, however, is not strong enough ‘to guide the development of volunteering as a public health promotion intervention’. Another study in England, which involved 10,324 participants over nearly 11 years, found that volunteering was associated with increased survival, at least for able-bodied volunteers.

- Being married may also help us live longer and healthier lives. That's the verdict of a 2018 study, although the greater benefits were for those couples whose marriage was ‘very happy’. Couples whose marriage was ‘not too happy’ lived no longer than those who had never married, were divorced, separated or were widowed.

- The creative arts may also have a protective effect on our health. A study of 6,000 people over 14 years in England found that people who engaged with ‘receptive arts activities’, such as visiting museums, art galleries, exhibitions, the theatre, concerts, or the opera frequently (every few months or more), had a 31% lower risk of dying.

|

As reported elsewhere on this website, and as Professor Sir Michael Marmot recognises, the four pillars of good health are clearly important too i.e. not smoking, drinking alcohol in moderation, eating a healthy diet and getting enough exercise. |

The value of education

Education has long been known to increase our chances of living longer. It isn’t just health researchers who have found this. Actuaries, who advise the insurance industry on how long pensioners are likely to live, and therefore how long they are likely to receive pensions, have known this for some time. The Longevity Bulletin 2012, from the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries, noted: ‘The evidence that education acts directly to improve mortality independent of socioeconomic status is said to be under-appreciated outside of demography’.

Not everyone has the same educational opportunities early in life. In the UK, however, there are many opportunities to return to education later in life as a mature student. One study published in 2011 suggested (with some qualifications) that men and women who leave school without any qualifications may be able to ‘catch up’ to some extent with more qualified people in terms of lowered risk of coronary heart disease (such as heart attack and stroke), if they obtain educational qualifications later on in life.

|

Another of Professor Marmot’s findings was that education appeared to reduce social inequality, increase people’s status and thereby improve longevity. |

For instance, in his book Status Syndrome: How Your Place on the Social Gradient Directly Affects Your Health, he reports that Kerala (a state in south-west India), Cuba, Costa Rica and Sri Lanka have all invested in education, including education for girls, and as a result their populations enjoy greater longevity than in most other developing countries.

Conclusions

Changing our socioeconomic status may not be easy, but being born into a family with low socioeconomic status doesn’t have to be a life sentence. Health and life expectancy can potentially be improved:

- Through our own achievements

- By being part of social networks and by integrating into society

- By volunteering

- By being happily married

- By involving ourselves in the creative arts

- Through education

_______________________________________________________

Other relevant articles on our website:

- Ageing: Adult Education – is it good for our health?

- Living longer: Is status a key to longevity?

- Living longer: How can we stay healthy longer?

- Living longer: Centenarians

- Mind: Stress

- Mind: Work and health

- Health Campaign: Healthy and wealthy

Reviewed June 2020. Review date May 2024